With the wave of anti-Asian attacks, Black Lives Matter, and race conversation boiling to the surface this past year, I’ve dug down deep and asked myself, ‘Why should we remember?” Why is learning our histories – the good, the bad, and the ugly – the latter which racist histories fall into, important? We’ve all heard the saying, ‘Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it’. But do we go the extra mile and ask why? Perhaps this will lead to a more holistic solution.

After deep soul searching, I’ve learned that I’m not here to make others feel bad about what happened in the past. The biggest gem I’ve learned is that it’s taught me more about myself. Specifically, the parts of myself I don’t like to see in the mirror. Fear of the unknown, of uncertainty, fear of the ‘other’ underlies racism. Certainly, amplified during COVID, I feel fear a lot. The biggest revelation came when I realized that I’m capable of being racist. I’d like to shed light on this in two ways: the first is through my heritage and community activism to promote the education of Japanese Canadian history. The second way is what my aunt and her best friend taught me about soul friendship.

As a third generation Japanese Canadian, my family and our community’s history – my history – was shaped by the Internment and Dispossession of Japanese Canadians: by the course of history. Both sides of my family were interned in 1942, lost everything material, their homes, their businesses, their boats, their livelihoods – life as they knew it. They rebuilt after the Internment, returning to Vancouver in 1949-50.

The Internment and Dispossession of Japanese Canadians was driven by racism: both systemic, and cultural. 22,000 Japanese Canadians were forcibly relocated to Internment camps from 1942-49 and dispossessed of everything they owned. They did not have the right to vote until 1949, and were limited to enter specific professions based on race. They were, by and large, not seen to be equal in the eyes of the law or socially.

Since then, there is no doubt that we, as a society, have made great strides towards equality and remembrance. Over the past several years, the Japanese Canadian community has made great efforts to mark physical sites and heritage conservation at Japanese Canadian historic sites. Starting in 2017, in partnership with the provincial government, the community installed Highway Legacy Signs at actual Internment sites and Roadcamp sites to physically mark where these camps were located. In 2019, the Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall became a National Historic Site. Many do not know that the Downtown Eastside, where the Japanese Hall is located, was a vibrant market village of 8000 Japanese Canadian residents, with over 400 businesses along Powell St. in Japantown before the war.

For both the Japanese Canadian community, as well as those not directly connected with this experience, acknowledging how and why the Internment and Dispossession happened moves the healing process forward. It helps to move the energy of shame, anger, heartbreak and betrayal caused by the trauma, which has been passed down to younger generations. It also is a vehicle to feel in our hearts the strength and joy of community, resilience and gratitude to parents and grandparents that got families through the hardship and moved society forwards to a better and more just place. It teaches us what racism is in all its ugliness and ultimately what grace can look like.

But I also took this one step further and asked myself, where am I racist? I could put myself in my grandmother’s shoes and feel what it must have felt like to pack her whole life into one suitcase with 10 kids. But I also asked myself the question, could I have been Prime Minister Mackenzie King who gave the final OK to turn the lives of 22,000 Japanese Canadians upside down? Could I have been the neighbour who felt it was wrong, but didn’t say anything because it wasn’t my business. Or the low level government clerk who didn’t question because he was just doing his job? When I let fear govern my heart, could I have done the same wearing different shoes?

The honest answer was an uncomfortable yes. There is no doubt that I have looked the other way and run away when I’m afraid. But when I use history as a mirror to see myself, I feel deep in my heart that social justice is not a God-given right, a rule or an idea. It is a privilege that comes with choice and responsibility. Each and everyday I can choose how to see another human being, whether I can stand in my neighbour’s shoes, no matter what the shoe looks like. By acknowledging that darkness exists in me, I can choose the light.

This connects to what my wise aunt dropped in to tell me the other day: choosing the light is easy, natural and pure. My Auntie Nobby (Nobuko), who’s been gone for about 30 years, was born in 1921 in Steveston, the eldest of 10 children. She contracted TB during the war, and she spent a greater part of the Internment recovering at the New Denver Sanitorium for Japanese Canadian patients. Out of the blue the other day, the daughter of her best friend from her childhood contacted me as she was writing a memoir about her mom.

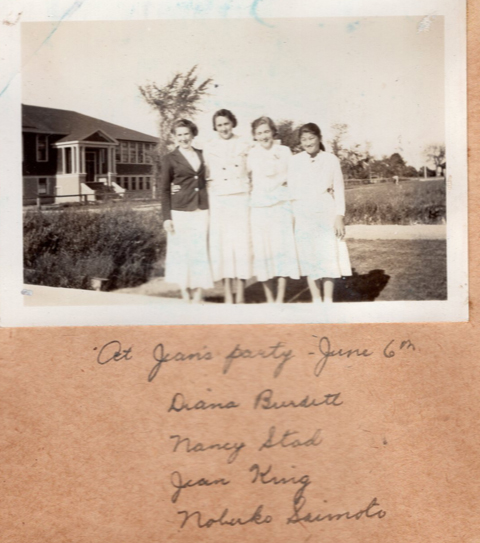

Through her daughter, for the first time I saw photos of my young aunt that her mom had saved all these years. The extraordinary thing about their friendship was the backdrop in which it took place. At age 4 (~1925), they became friends and grew up together. Though my aunt didn’t speak English, and Diana Burdett didn’t speak Japanese, they became best friends. Diana, my aunt and the family’s two dogs, used to hang out together.

Diana went to school with my aunt at Lord Byng Elementary in Steveston. She was the only little white girl to sit through Japanese School class after public school to learn Japanese with my aunt. Apparently, the Japanese teacher did not acknowledge Diana in class, but did not kick her out either. Even through the war years, they continued to write letters and exchange photos, one of those being a photo of my aunt recuperating at the sanitorium. Diana’s father had tried to help out the Saimoto family by renting the family home that was confiscated by the government for $10 per month to prevent looting and its forced sale. With life’s twists and turns, because Diana had learned Japanese as a little girl, she eventually worked for the US Occupation Forces in Intelligence as a translator post-war in Tokyo.

Despite the noise of war, Internment, racism, and post-war life, they remained friends until their deaths. Two little girls learning each other’s languages and culture, seeing each other only as soul friends. My Auntie Nobby and Diana and the Saimoto & Burdett families chose the light. It was that simple.

Why should we remember? For me, bottomline is that I’ve learned to be more honest with who I am. From here I can make a conscious choice. I can choose love, not fear; light, not darkness; unity, not separation. The stories of my family’s history, of my aunt’s and Diana’s story, have taught me about myself and heart-based solutions. It’s from here that I have more deeply come to love Canada, and appreciate the privilege and responsibility of citizenship, and of being human. This to me, is the legacy of remembrance.

Laura Saimoto, heritage activist

Image supplied by author.

–