Preface: In 2020, I was invited to reflect on my experiences with racism, inclusivity, and equity. The result was Erasure. My perspective then and now is as a racialized person, who is also a descendant of a head-tax payer.

How will 2021 be remembered? It is a year of significance in Canadian and British Columbian history. The month of July marks the 150th year of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation. Commissions and grants were given to organizations in advance to commemorate the occasion; however, no one could have anticipated the association of 2021 with a continued global pandemic and a visitation to a colonial past that collides with contemporary history—a reckoning with erasure and racism.

Yet, it was anticipated—by Indigenous Peoples and racialized pioneer Canadians. Canada’s story is shaped through the eyes of those who officially and unofficially are its gatekeepers; until recently, they were most often ‘white.’

gatekeeper noun : a person who controls access (Merriam-Webster)

Since May 27, 2021, when Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc revealed that the Kamloops Residential School site held the remains of 215 unmarked burials, Canada has learned of additional locations: St. Eugene’s Mission School (BC), Marieval Indian Residential School (SK), Kuper Island Residential School (BC), and Delmas Indian Residential School (SK). None of this should be a surprise, yet for many non-Indigenous Canadians it is. There will be more recoveries; Volume 4 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports, “Canada’s Residential Schools: Missing Children and Unmarked Burials” (2016), makes this very clear. Confederation brought federal policies to regulate Indigenous Peoples from coast-to-coast-to-coast. Because these policies did not affect the dominant population, where ‘white’ society is the standard, to many it was as if this did not happen.

Few seem to know about this dark past even though the stories have long been told and are finding their way into a variety of media, such as in film and literature. Why? I could simply say, “it needs to be taught,” which is true; however, let me take one step back. Besides government, who are the gatekeepers of history? Many places, even a ‘village,’ will have a historical society and/or a museum and archives. At a community level, this is where a story will be recognized and valued as it directly reflects the place. Is it the story of the coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, or about the Nanaimo Indian Hospital?

Unfortunately, there is a degree of amnesia. In BC there were 18 residential schools spread throughout the province, yet in a response resembling denial, these unsettling stories are neither told nor acknowledged by ‘white’ society. A residential school may not have been in your area; however, survivors likely make their home in your village, town, or city. In other words, this story belongs to my community and yours; it is our collective Canadian history.

The composition of early colonial settlements prior to and post-Confederation may differ from their current-day population. Towns and villages today might assume that diversity is a dichotomy of ‘white’ and Indigenous, with the assumption of racialized immigrants as recent arrivals. Forgotten are the labourers who breathed life into the numerous resource-based communities. Many of these extractive industries—whether mining, fishing, or lumber—relied on a marginalized and/or racialized work force.

Consider the early Chinese, Japanese, and South Asian pioneers who were all part of these industries. Were their contributions and stories valued?

How they were remembered is even questionable. Valued as ‘cheap’ labour, but also expendable, they often were viewed as nameless individuals—in essence, erased from the story of building BC and Canada. The classic example is the photo of Donald Smith striking the last spike at Craigellachie. Though thousands of Chinese labourers lost their lives in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, not one was to be seen in this most famous image.

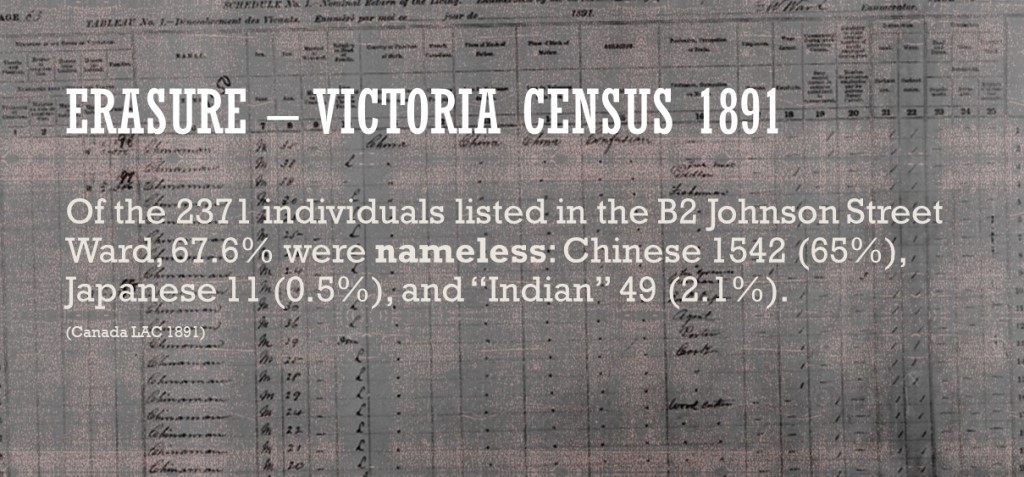

In some cases, racialized populations were not sufficiently valued to warrant the effort to be accorded a name. In the 1891 Canada Census, the Johnson Street Ward of Victoria had no Chinese names; they were simply listed as ‘China man/woman/boy/girl.’ This was true of Japanese and Indigenous Peoples, as well. They were without personhood.

In these, omission and erasure were purposeful, as noted in contemporary articles (here and here)revisiting Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce’s analysis of residential school conditions (The Bryce Report). The evidence he presented before government was ignored, so here we are in 2021 confronted with multiple chapters of Canada’s story that elicit pain, shock, and horror.

Gatekeepers. Yes, they can be government agencies (federal, provincial, and municipal) or religious organizations. Information is recorded, analyzed, kept, hidden, forgotten, ignored, and sometimes lost. As well, gatekeepers at a more local level are represented by historical societies, and museums and archives.

What do gatekeepers do and why does it matter today? The role of museums, supported by historical societies and archives, is to amplify the voices and stories of the community. ‘Pioneer’ history was a ‘colourful’ one; it was multicultural before multiculturalism became policy in 1971. Who was that cook or servant standing to the side in the family photo of the prominent ‘white’ community member? Who were the many workers in the local sawmill, cannery, etc. that made its ‘white’ owner successful? Racialized immigrants were a part of the fabric of this land before its inception as a province and their contributions continue to today. In 2021, it is time to stop this erasure of those who were subjected to racist colonial policies.

When erasure and amnesia of the past occur, it affects how contemporary history—of Indigenous Peoples and racialized settlers—is viewed and understood. Racist policies ‘gave permission’ to erase segments of Canada’s story. Now is the time to take on the task of confronting this past; between researchers and gatekeepers, we need to recover, to remember, and to tell our community’s stories— truthfully and unapologetically.

Imogene L Lim, PhD

Anthropology

Vancouver Island University

About the image:

Census enumerators are expected to list names in full, yet BW Ward withheld identities. As an official document, B2 Johnson Street Ward includes 44 pages of nameless individuals from China. Lives were ‘erased’ by this official gatekeeper. This image is based on one used in a presentation of an essay of the same name, It’s 2017: Echoes of the Past (BC Studies, 2017).

–