- Heritage 101

- Advocacy

- Accessibility for Historic Places

- Climate & Sustainability

- Cultural Maps

- Heritage Place Conservation

- Heritage Policy & Legislation

- Homeowners

- Intangible Cultural Heritage

- Reconciliation

- Indigenous Cultural Heritage

- Setting the Bar: A Reconciliation Guide for Heritage

- 1. Heritage and Reconciliation Pledge

- 2. Acknowledging Land and People

- 3. Celebrating Days of Recognition and Commemoration

- 4. With a Commitment to Learn

- 5. Committing to Strategic Organizational Diversity

- 6. Mission-Making Room for Reconciliation

- 7. Possession, Interpretation, Repatriation and Cultural Care

- 8. Shared Decision Making

- 9. Statements of Significance and other heritage planning documents

- 10. Heritage Conservation Tools, Local Government Act

- Racism: Do Not Let the Forgetting Prevail

- Taking Action: resources for diversity and inclusion

ICH Inventorying: Step 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 1: Community involvement

Community members are the creators and experts of their Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). They are responsible for its transmission and for keeping their ICH alive. Consequently, the holders are not simple informants but instead they are protagonists in the inventorying process, playing a central role in planning and implementation.

In this context, non-community members are co-facilitators and supporters in the process.

Who makes up the community?

“Community” is a complex, fluid, and broad concept, which has been the centre of wide debates in the social and human sciences. There is no single conceptualization that is universally accepted. For the purposes of the 2003 Convention, “community” encompasses those who create, maintain, and transmit intangible cultural heritage and recognize it as their heritage.

There are three main aspects that permit the widest conceptualization of community in the ICH context:

- Sense of belonging,

- Linkages among practitioners

- Sense of identity.

Variety of the community members

“Community” has many different participants, each with singularities, attributes, and roles. Sometimes, however, participants are not given opportunities to express themselves due to their relationships with the community or other participants. Reasons for this could include differences in age and/or gender, socioeconomic backgrounds, and the participants’ roles in ICH manifestation.

Community-based inventorying must include multiple voices at the community level, recognizing that every voice has a key role in the identification and transmission of ICH.

When starting, it is necessary to ask, “Who should be involved? In what role?”

What is participation?

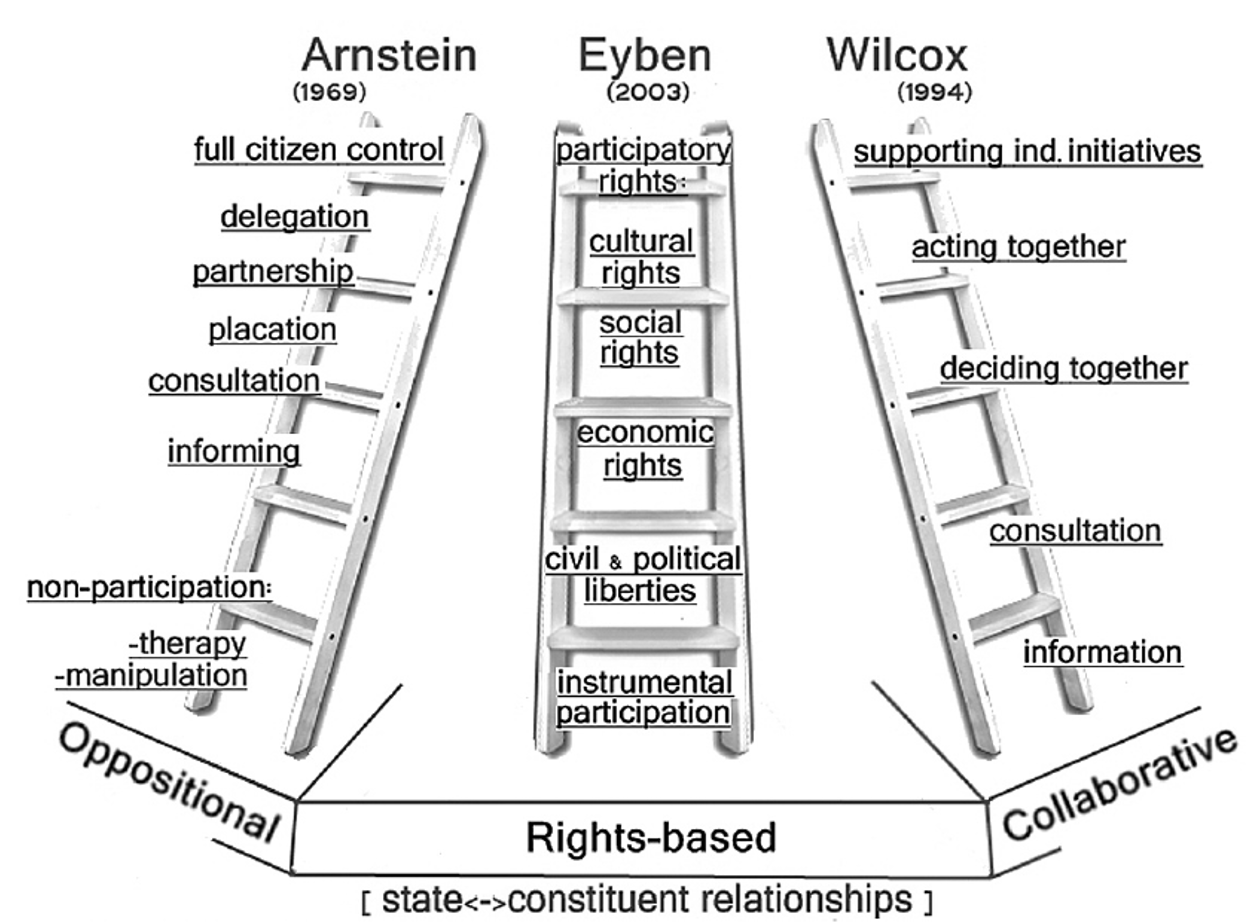

As with the concept of community, “participation” is also broad, as it has diverse meanings for different authors and specialists. However, it is common to find participation theories that associate participation with a ladder in which each step represents stages or levels of participation ranging from no participation to full participation.

The following picture represents some of these visions:

Models of participation. Three models of participation (Arnstein, 1969; Eyben, 2003; Wilcox, 1994) are summarized using the common visual metaphor of the ladder. In: Aylett, 2010.

Despite the differences between the theories and conceptions about participation, the main aspect is the role of the community in decision-making. In this guide, participation is seen as a process in which decision-making can vary according to the characteristics of communities and so it may be achieved in different ways according to the context but always based on the centrality of the community.

Regarding the general work with communities, the 2003 Convention Committee adopted 12 Ethical Principles that are widely accepted as a good practice and serve as a basis for developing a code of ethics when working with local communities. They were inspired by the existing international normative instruments protecting human rights and the rights of indigenous peoples. They aim to guarantee transparency and respect, and they ensure the community directly benefits from the inventorying process.

One of the most important tools to guarantee transparency and equity in the inventory process is free, prior, and informed consent. This is not a document to be signed by some community representatives. Instead, it is a process that implies constant dialogue and comprehension about the decisions that should be made at each step of the process. Beyond that, the procedures to obtain the consent must reflect the inclusivity throughout the inventory process.

The 12 Ethical Principles

- Communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals should have the primary role in safeguarding their own intangible cultural heritage.

- The right of communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals to continue the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge and skills necessary to ensure the viability of the intangible cultural heritage should be recognized and respected.

- Mutual respect, as well as a respect for and mutual appreciation of intangible cultural heritage, should prevail in interactions between States and between communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals.

- All interactions with the communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals who create, safeguard, maintain and transmit intangible cultural heritage should be characterized by transparent collaboration, dialogue, negotiation, and consultation, and contingent upon their free, prior, sustained, and informed consent.

- Access of communities, groups, and individuals to the instruments, objects, artefacts, cultural and natural spaces and places of memory whose existence is necessary for expressing the intangible cultural heritage should be ensured, including in situations of armed conflict. Customary practices governing access to intangible cultural heritage should be fully respected, even where these may limit broader public access.

- Each community, group, or individual should assess the value of its own intangible cultural heritage and this intangible cultural heritage should not be subject to external judgements of value or worth.

- The communities, groups, and individuals who create intangible cultural heritage should benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from such heritage, and particularly from its use, research, documentation, promotion or adaptation by members of the communities or others.

- The dynamic and living nature of intangible cultural heritage should be continuously respected. Authenticity and exclusivity should not constitute concerns and obstacles in the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage.

- Communities, groups, local, national and transnational organizations, and individuals should carefully assess the direct and indirect, short-term and long-term, potential and definitive impact of any action that may affect the viability of intangible cultural heritage or the communities who practice it.

- Communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals should play a significant role in determining what constitutes threats to their intangible cultural heritage including the decontextualization, commodification and misrepresentation of it and in deciding how to prevent and mitigate such threats.

- Cultural diversity and the identities of communities, groups and individuals should be fully respected. In the respect of values recognized by communities, groups, and individuals and sensitivity to cultural norms, specific attention to gender equality, youth involvement, and respect for ethnic identities should be included in the design and implementation of safeguarding measures.

- The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage is of general interest to humanity and should therefore be undertaken through cooperation among bilateral, sub-regional, regional and international parties; nevertheless, communities, groups, and, where applicable, individuals should never be alienated from their own intangible cultural heritage.

(source)

To know more about free, prior, and informed consent, see:

- Free, Prior and Informed Consent in Canada: Towards a New Relationship with Indigenous Peoples | Insights | Torys LLP

- Perez Lopes, Enrique. Who does consent? UNESCO – Culture and Development Magazine. 12, 2014, pg 25-30 https://webarchive.unesco.org/20151105171733/http://www.unesco.lacult.org/lacult_en/docc/CyD_12_en.pdf

To know more about Ethical Principles to work with Living Heritage, see:

To know more about community concept in Living Heritage context, see:

- JACOBS (M.), CGIs and Intangible Heritage Communities, museums engaged, in: DJERIC (T.) a.o.,(eds.), Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage. Towards a Third Space in the Heritage Sector. A Companion to Discover Transformative Heritage Practices for the 21st Century, Brugge, Werkplaats Immaterieel Erfgoed, 2020, pp. 38-41, ISBN 978 94 6400 720 6. Available in: https://www.ichandmuseums.eu/en/toolbox/book-museums-and-intangible-cultural-heritage